Imagine if you could:

- Meet your everyday needs — food, medicine, education — without having to own a car or drive anywhere

- Live a healthy life — including physical activity and time in nature — simply by going about your daily routine

- Know the names and stories of the people who live around you

These are just some of the many benefits of an urban planning concept that’s rapidly entered mainstream public discourse in recent years: the 15-minute city.

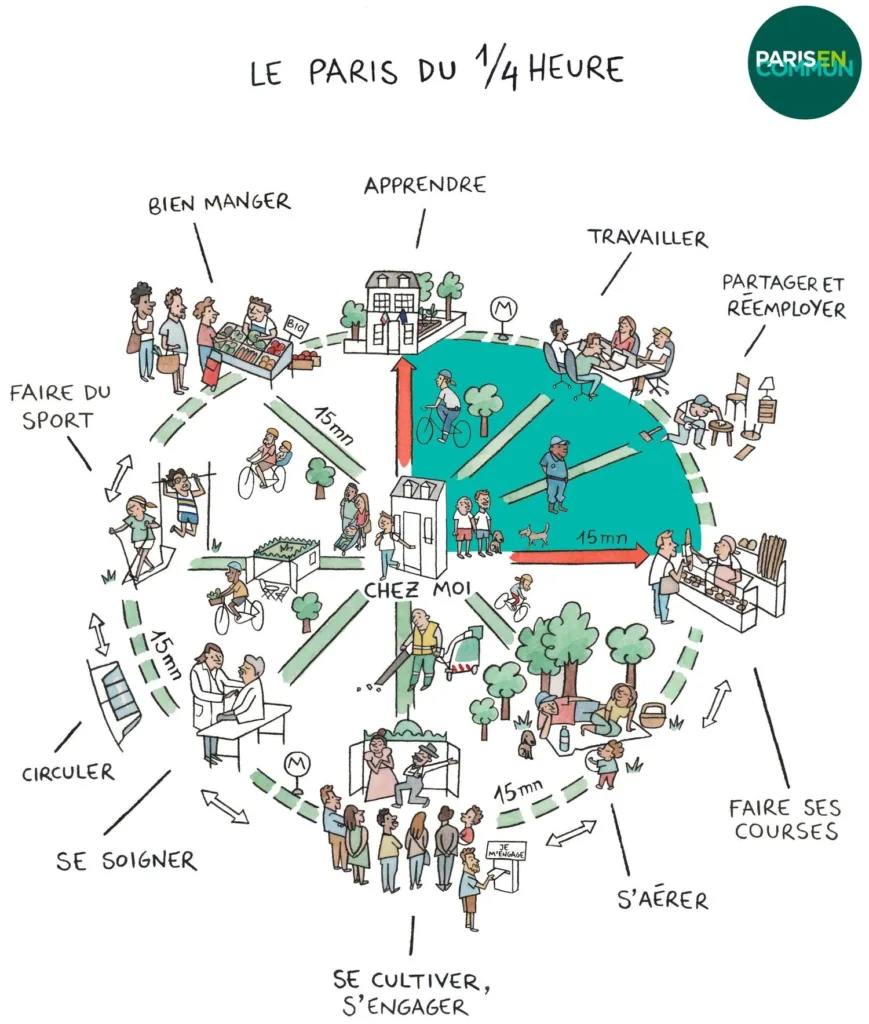

The idea is both simple and transformative: all of us should be able to meet our everyday needs — specifically, living, working, supplying, caring, learning, and enjoying — within a 15-minute radius of where we live, without having to drive. While the idea of building hyper-local communities is nothing new, with versions dating as far back as the early 20th century, the term “15-minute city” was coined by urbanist Carlos Moreno, a professor at Panthéon-Sorbonne University in Paris in 2016. The city is also where the concept began to receive international attention, after it became a cornerstone of mayor Anne Hidalgo’s successful re-election campaign in 2020. Since then, Ottawa, Edmonton, Milan, and other cities have begun to consider adopting the approach, citing benefits for our physical health, the environment, and housing affordability.

But the impact of the 15-minute city doesn’t stop there. It also makes where we live more conducive to one of our most basic needs: social connection.

Between sprawling suburbs and loud, fast-paced cities, many of us in the US and Canada know that it can be difficult to even recognize who your neighbours are, let alone have the space or purpose to regularly interact with them. According to a Pew Research Center survey in 2018, more than half of Americans (57%) know only some of their neighbours, while a Nextdoor survey in the same year in Canada found that 38% of Canadians know only one or two of their neighbours.

While changing how we build our communities is no silver bullet, studies have shown that pedestrian-oriented design and mixed-use zoning — key features of the 15-minute city — support social interaction by creating “bumping spaces,” or places in our communities where we formally or informally meet and interact with our neighbours. And this doesn’t even get at the most obvious relational benefit of the 15-minute city: more time.

In Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, political scientist Robert Putnam estimates that an additional ten minutes of commuting cuts community involvement by 10%. More time and energy spent travelling to and from work, he suggests, means less time and energy to connect with family, friends, and neighbours. A more recent study using data from the National Household Travel Survey in the US came to a similar conclusion: commute times of 20+ minutes have a negative impact on the number of socially-oriented trips people take, with the strongest correlation among those commuting for more than 90 minutes. Reducing vehicle dependency through the 15-minute city paves the way for more time with the people and in the places we care about.

Car-centric development not only impacts the social connectedness of people in traffic, but also of the people around it. This was famously documented by Donald Appleyard, who was a professor of Urban Studies at UC Berkeley. Appleyard is known for his study in the late 1960s of the effect of traffic on social connectedness in residential streets. After comparing three streets in San Francisco with traffic volumes of 2,000, 8,000, and 16,000 vehicles per day, he found that those who lived on the street with the lowest traffic volume had three times as many friends on the street as those on the street with the highest volume of cars. Appleyard also studied the spots on the street where people gathered, and found that the street with the least traffic had many more than the street with the most traffic. Here, residents noted that “people are afraid to go into the street because of the traffic,” suggesting that it does directly impede social interaction.

But the significance of the 15-minute city is bigger than its direct effects on what we can access and the ways in which we can access it. As Healthy Places by Design notes, social isolation “is not a personal choice or individual problem, but one that is rooted in community design, social norms, and systemic injustices.” Our will to form deeper connections with our neighbours can only go so far without the time, space, or purpose to bring it to life.

Unfortunately, the 15-minute city has been mired in controversy in recent months, as conspiracy theorists have co-opted the idea as proof of overreaching government surveillance and control, limiting their freedom to move around. And while government agencies could do a better job of tackling misinformation and explaining what exactly 15-minute cities are — and, more importantly, what they aren’t — proposing, the concept boils down to the belief that a car should not be a prerequisite for living a healthy, sustainable, and socially connected life.

Of course, as with any transformative approach to the built environment, there are limitations and trade-offs. The 15-minute city may not be the most relevant idea to those of us living in rural communities, where infrastructure to support active transportation isn’t as developed or even feasible as it is in urban centres. And in pursuit of designing more livable places, we cannot displace marginalized communities through gentrification, allowing only a select few to reap the benefits of a 15-minute city.

But in the midst of a climate crisis, record-breaking traffic deaths, and an epidemic of loneliness, it’s clear that we need to fundamentally reimagine how we build our communities and go about our daily lives. Making it easier to connect with the people and places that matter most to us seems like a good place to start.

P.S. Our sister organization, The Foundation for Social Connection (F4SC) is currently working on the Built Environment edition of its Systems Of Cross-Sector Integration and Action across the Lifespan (SOCIAL) report. If you would like to get involved, please contact Abigail Barth, F4SC’s Research & Innovation Program Manager at abigail@social-connection.org.